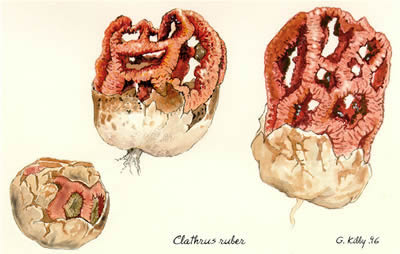

Clathrus ruber, the Basket Stinkhorn

“I Stink, Therefore I Am.”

Talk about unwanted neighbors. A seductively beautiful, but devilishly foul-smelling fungus may be coming soon to a neighborhood near you. She’s a real hottie, a heat-seeking Mediterranean redhead, spreading north in Europe, and traveling across the seas to hospitable new homes on both coasts of North America.

© photo courtesy Hugh Smith

Meet Clathrus ruber, or as intimates call her, the “Basket Stinkhorn.” And stink she does, like rotten meat on a hot day. Repugnant to you, perhaps, but the smell is catnip to flies. They flock to her foetid scent, feed upon the spore-impregnated greenish-black gleba, and soar off, spreading stinkhorn spores in their wake. But before I bid adieu to my fungal anthropomorphizing, I bid you follow this link to French artist Diane Özdamar’s clever painting of a Clathrus ruber nymph… Ooooo la la!

Fantasy aside, the reality of this mushroom is no less striking. Like an amanita, Clathrus ruber hatches from an egg-like universal veil. At the base of the egg is a thick mycelial “root”. If you were to slice this egg in half, you would find a whitish embryonic mushroom, shaped like a compacted open-work basket, with slightly darker, barely scented gleba on its inner surface. At this stage, the mushroom is edible (according to some of, shall we say, less refined sensibilities). Once it has developed the stench of death, it is suitable only for feeding flies.

© photo courtesy Hugh Smith

As the young mushroom matures, the smooth white egg takes on geometric patterns. The body of the mushroom expands and the production of carotene stains it red-orange to pink. The membranous veil tears, and a bizarre fungus is hatched. Remnants of the veil form a cup or volva at the base. Spores are produced within the foul-smelling, dark-green, gooey gleba.

© photo courtesy Ari Kornfeld

Since their spores are not usually spread by the wind, natural dispersal is limited to the distance that a fly or other vectors can travel, or more widely, through the inadvertent transport by humans through transplanted plant material and mulch. Stinkhorns are saprobes, digesting all manner of organic debris, and grow well in wood chip habitat or other composted areas. They prefer to live in moist, protected locations. They are somewhat invasive, and can take over landscapes, making outdoor activities inhospitable during the fruiting season. One unhappy homeowner inherited a backyard where Clathrus ruber had been inadvertently introduced by the previous owners. Over the span of only eight years, it spread across 3000 square feet! Too bad for them. David Arora claims that Clathrus ruber is the foulest smelling of all the stinkhorns.

If its look, and smell, and unusual method of spore dispersal aren’t enough, this mushroom is also apparently bioluminescent. Ramsbottom (“Mushrooms and Toadstools, A Study of the Activities of Fungus”) refers to experiments performed with a variety of suspected light emitting mushrooms. Luminescence provided by a Clathrus ruber was strong enough to expose a photographic plate through an intervening piece of cardboard! But I will have to take Ramsbottom’s word for it. Although you can view examples of mushroom bioluminescence in the privacy of your own home (or closet), it is unlikely that you would be able to remain for very long in a small, dark space with a mature Clathrus.

The basket stinkhorn’s bright coloration and intriguing openwork basket shape make it an object of curiosity wherever it occurs. It almost seems out of place in a natural setting, looking like a day-glo colored whiffle ball that has come to rest in the garden. Once this mushroom has matured, the fruit body is extremely delicate and short-lived, and does not tolerate disturbance. After it has burst from its egg, it only lasts a day or two before its spores have been dispersed (as well as the smell) and the fruit body shrivels, leaving the mycelial mat behind in the ground, to spread itself and future fruit bodies to new locations.

© photo courtesy Candace Simpson 2007

Originating in the Mediterranean region, these mushrooms prefer temperate climates, but are believed to be spreading north with global warming. They are still a rare component of the mycota of England proper, but are now common on the English Channel Islands in wood chip habitat, and have even been reported from the shores of Lake Geneva, Switzerland. Crossing the Atlantic and landing in Florida, Clathrus ruber is now fairly common in that state, and has also been confirmed in Georgia (according to Dr. James Kimbraugh, University of Florida, Gainesville and Dr. Michael Beug).

Clathrus ruber can be found throughout the San Francisco Bay Area. It has appeared regularly in the landscaping beds at the Strybing Arboretum for at least the past two decades, and can now be found in surrounding suitable habitat, at all times of year when conditions are conducive. In the past few years, large fruitings have been reported from Marin County. They have recently spread their foul scent across the campus of Cabrillo College, in Santa Cruz County, and just last week, they made their appearance in the Palo Alto Demonstration Garden, in Santa Clara County.

© Drawing provided courtesy of Geoffrey Kibby

A number of fine photos of this mushroom, in all stages of growth, were provided by several photographers (see photo credits). But they could just hold their noses, click and run. Most impressive was a beautifully detailed illustration by Geoffrey Kibby, editor of the fine English journal, “Field Mycology.” What fortitude it must have taken to sit and paint his stinking subject. Kibby wrote me that Clathrus ruber was still very much a rarity there, despite global warming, and that the specimens had been collected from a churchyard in the southwest of England. The devil you say, Geoffrey.

© Debbie Viess

back to top

back to top