Amanita phalloides: Invasion of the Death Cap

Amanita phalloides, commonly called the Death Cap, is a strikingly beautiful mushroom and the number one cause of fatal mushroom poisonings worldwide. Originally found only in Europe, it has proved to be highly adaptable to new lands and new mycorrhizal hosts. Death Caps now occur around the world, from Australia to South America, but nowhere have they found a place more to their liking than in the oak-strewn State of California.

Amanita phalloides are believed to have first arrived in California on the roots of imported, ornamental trees, most likely Cork Oak (Quercus suber). They have since successfully branched out to form countless mycorrhizal associations with native coast and interior live oak. If we can assume (and trace through the literature and herbaria) that its earliest arrival in Central California was around 1938, it is remarkable to think that in a little over seven decades, Amanita phalloides can be found throughout California, from the Sierra foothills to the Channel Islands, wherever live oak is found. Death Caps have recently been documented growing with pine in Marin County (pine is its preferred host on the East Coast of North America) and with Tanoak (Lithocarpus densiflorus) in Mendocino County, and may be expanding their California tree hosts.

|

|

| Amanita phalloides at Tomales Bay Harvard study site | Amanita phalloides in Henry Cowell State Park, Santa Cruz |

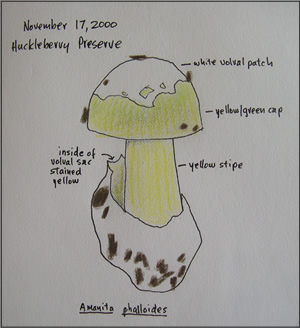

Like all amanitas, young Amanita phalloides are completely covered by a tissue called a universal veil. This tissue is tough and membranous. As the young mushroom expands, the veil tears cleanly. This normally results in the mature mushroom having a bald cap. Color in many amanita species can be quite variable, but a classic phalloides will have a greenish-yellow cap with visibly embedded radial fibrils. Death Caps can also be green, yellow, brown or tan or rarely white, and often take on a metallic sheen with age and drying. The white gills, which normally do not quite meet up with the stem or stipe and are called free, are first covered by a partial veil. This veil drops as the cap expands, to form a delicate skirt or annulus around the stipe.

Amanita phalloides spores are white in mass, globose and thin walled, and will stain blue if exposed to the iodine-based Meltzer’s solution. The stipe can be either white or yellowish, and ends in a distinctively bulbous base. This base is closely covered by a membranous sac. All of these features can be easily lost if not carefully collected, so it is important to dig up the entire mushroom when making your identifications. The odor of a Death Cap can be pleasant in youth, or a foul, decayed protein odor in age. Those who have eaten this mushroom call it delicious.

|

|

| Amanita phalloides: note yellow color on stipe and inner volva | Young Amanita phalloides: scarily similar to an edible Coccora |

In the greater Bay Area, Amanita phalloides can be found at all times of the year. Death Caps are most abundant during the heart of our fall and early winter rainy season, but they can also appear through late spring, and even during our rainless summers, in areas of coastal fog drip or in stands of irrigated oaks. According to Dr. Anne Pringle (formerly at Harvard University, now at University of Wisconsin, Madison) who has been studying this phenomenon, Death Caps in California are considered to be the first recorded instance of an invasive mycorrhizal mushroom (there are many instances of saprobic mushrooms spreading into new areas, especially into man-made habitats like wood chip beds).

Dr. Benjamin Wolfe (former post-doc in the Pringle Laboratory at Harvard, now at Tufts University) has discovered that Amanita phalloides look and behave differently in California. They form the largest fruit bodies here of any found worldwide, and they are prolific fruiters, with dozens of mushrooms sometimes found beneath one host tree. They also produce unusually abundant mycorrhizal associations. Most hyphal/root connections, including those of phalloides in their native land, can be difficult to locate. California Death Caps have mycorrhizal nodes that are readily located on the roots of their host trees. It is theorized that they may be crowding out native species, although that theory has not been substantiated. There is also a question as to whether or not these mushrooms are “cheating” their host tree, by taking sugars without giving much back in return, but this has also proved to be quite difficult to study, either in the lab or the field.

Deadly Poisonings and Promising Treatment

Death Caps are not merely an ecological quandary. They produce the most serious types of mushroom poisonings, which can result in liver failure or even death. Amanita phalloides, as well as their deadly native California relative, Amanita ocreata, contain acutely toxic amatoxins, a highly stable protein that the body has great difficulty in completely eliminating. Modern medical treatments have reduced the death rate for these types of poisonings to around 15%, but even if you survive, it is an excruciatingly painful type of poisoning, and can cause permanent damage to your health and liver.

The most promising new treatment for amatoxin poisonings is intravenous silibinin, a derivative of milk thistle. Silibinin (see below) protects the liver by preventing the uptake of amatoxin by the liver cells. Once the amatoxins are eliminated from the body, the liver can quickly recover. Injectable silibinin has been used in Europe to treat amatoxin poisonings for two decades.

A long-term clinical trial of intravenous silibinin has just begun in the US. For more information on the clinical trial, and for hospitals and physicians to enroll amatoxin poisoning victims, click here. Immediately call the Legalon® SIL hotline: 866-520-4412 if you have a suspected case of amatoxin-mushroom poisoning.

|

|

| Amanita phalloides in Albion, CA on tanoak © Photo by Douglas Smith. |

Amanita phalloides on a cutting board: Don't let this happen to YOU! © Photo by Jason Hollinger. |

If you forage for wild mushrooms for the table here in California, you MUST learn the characteristics of this common and spreading, deadly mushroom. Mushrooms are infinitely mutable, and colors and shapes and even areas of occurrence are constantly changing. A few unfortunate folks every few years make a fatal mistake. The reasons for mistakenly eating a deadly mushroom are as variable as the mushrooms themselves, and we really don’t know why without asking the victim. Education is crucial to preventing poisonings.

So spread the word and be careful when collecting wild mushrooms: A mistaken dinner-table ID with Amanita phalloides could be your very last supper!

© Debbie Viess

Additional Resources

Oral silibinin, which also has a hepato-protective benefit, has sometimes been used to treat deadly amanita poisonings. Unfortunately, oral medications cannot be absorbed by the gut during the extreme bouts of vomiting and cholera-like diarrhea symptomatic of amatoxin poisoning.

- Information on the first use of intravenous silibinin in North America

- Information on a new FDA study and treatment using silibinin

- Information on common, amatoxin containing Bay Area mushrooms

- Information on Amanita phalloides and other amanitas worldwide can be found at Dr. Rod Tulloss’ fine Amanita Studies website

- The North American Mycological Association has extensive information on mushroom poisoning syndromes and a registry of mushroom poisoning incidents.

back to top

back to top